Motivation in Utopia

Hey folks,

It's been a hot minute. As promised, I'm doing a new issue of the newsletter every so whenever. So true to my rigorous timetable, I present to you one of my favorite sets of experiments. Let's rewind a few decades to when researchers created a utopia for rats...and then, in true human fashion, completely over-interpreted its implications on the supposed doom of human civilization.

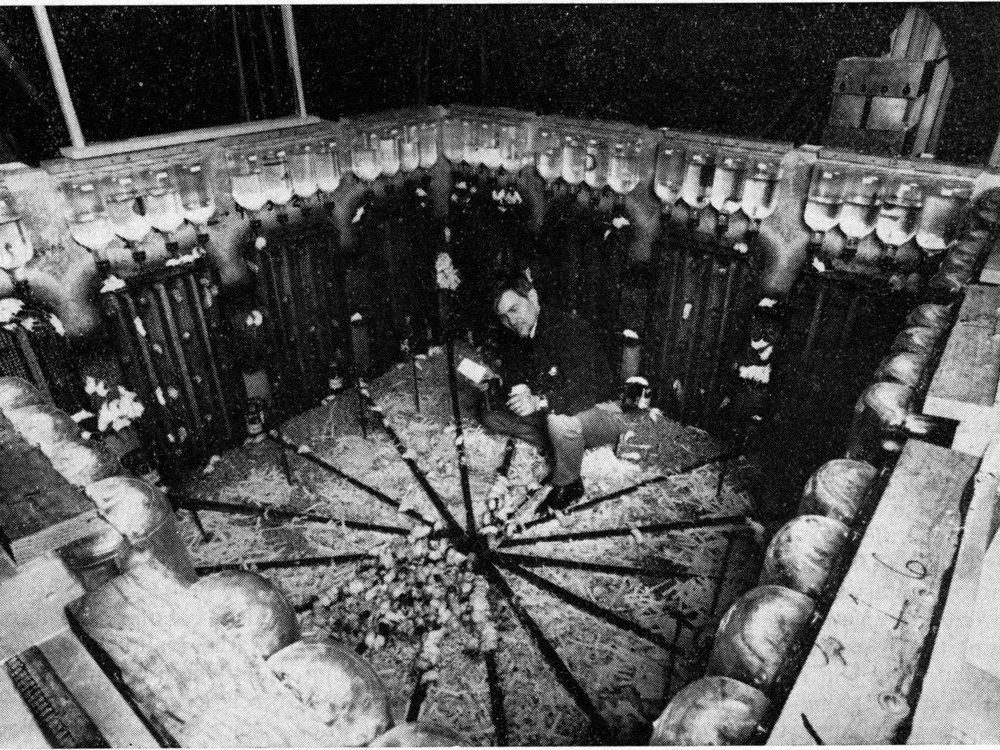

In a small town in Maryland in 1947, a scientist named John built a giant rat enclosure in a barn. This place was basically a Disney World for rats. It was huge—estimated to hold 5,000 rats—with plenty of food, water, and toys. Everything short of princesses and cotton candy.

But the population leveled off at a mere 150. Infant mortality climbed up to 96% as mothers neglected their children and aggression spiked. Mating became unimportant. Submissive rats became despondent. So with all that material abundance combined with growing (and ultimately shrinking) populations, the reason for the decline in numbers had to be psychological.

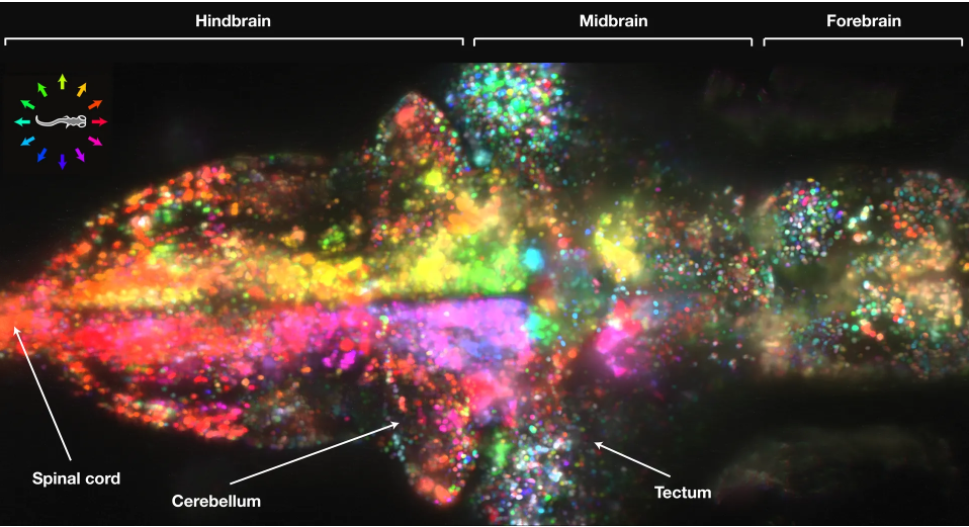

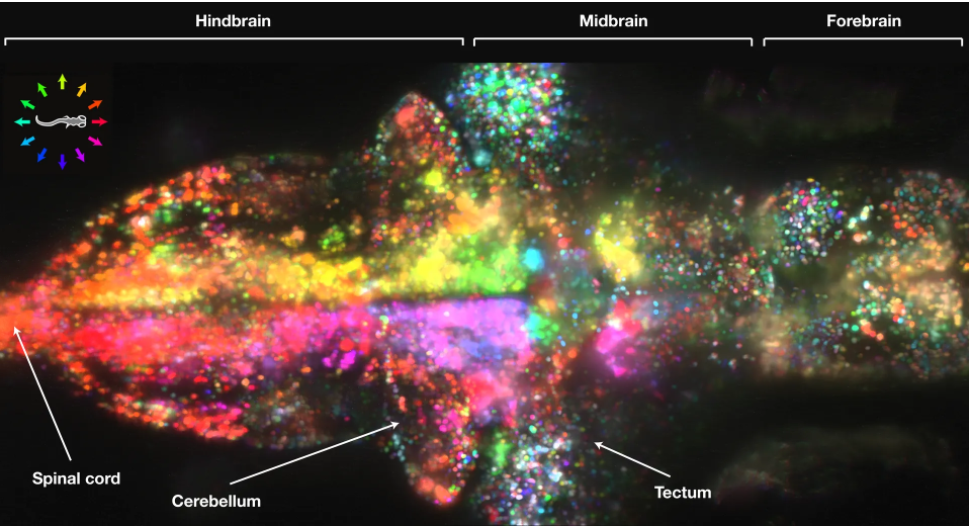

Why make rat utopias? Research often involves "animal models" where animals are chosen (or genetically engineered) for traits that represent phenomena seen in humans. Need an autistic fruit fly? There's a SKU in a scientific version of Amazon.com for that. Need to photograph a brain in action? Grab a zebrafish whose transparent skin allows you to photograph their brain as they swim.

And need a depression resilient mouse? Easy. Just take hundreds of mice, try to drown them in a pool, and those who take the longest before they give up trying to swim are more depression-resilient. (Not all animal models are this cruel, obviously, but that one is tough to swallow.)

So a rat utopia, believe it or not, can be used as a model of motivation. In a more pessimistic light, it can also be a model of societal collapse. It helps us answer the question of how we deal with material abundance combined with growing population numbers.

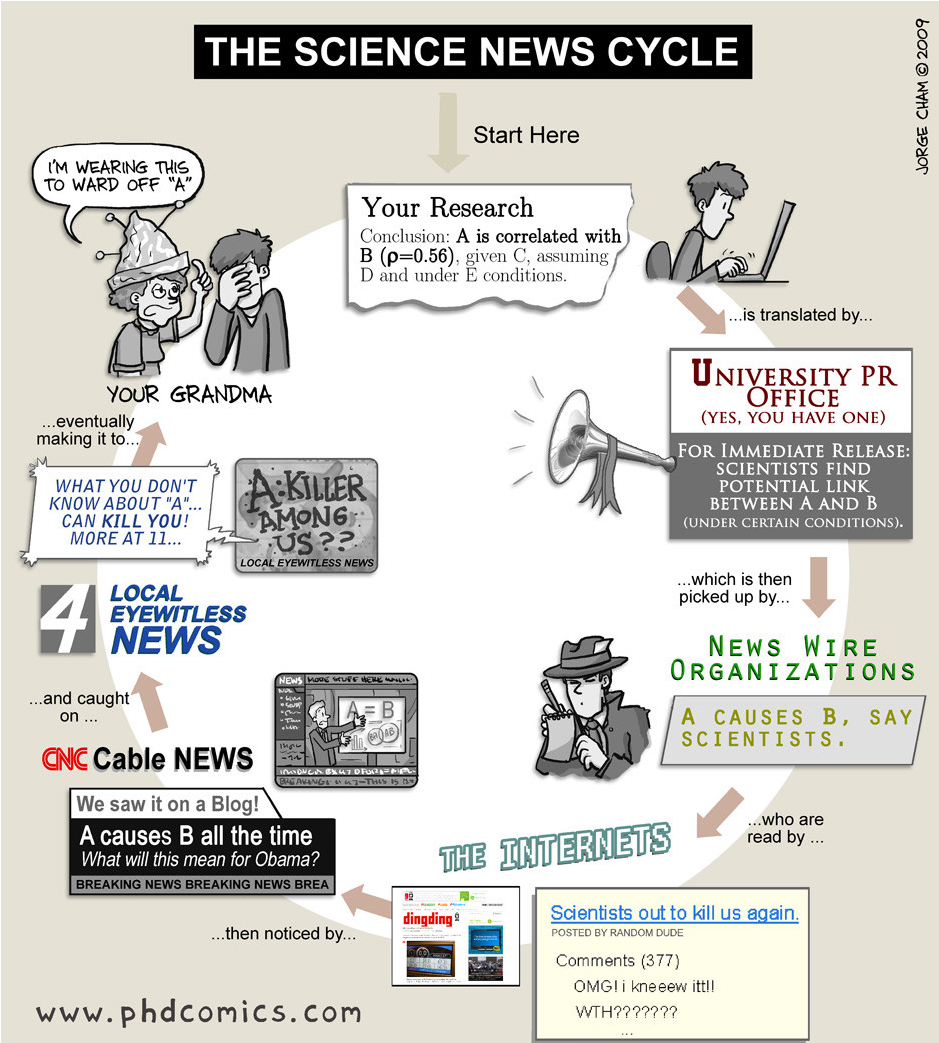

After a few scientific publications came the news headlines that society was going to collapse because these rats stopped mating. Without the pressures of resource scarcity or without personal space, how could these animals possibly act as stand-up citizens of their rat utopia? And what might this mean for the future of humans? (Spoiler alert: there was a lot of doom and gloom.)

There were follow-on studies on humans, too. One found that being in a crowded high school but with plenty of food in the cafeteria had no influence on behavior, stress, aggression, etc. So maybe rats aren't perfect models of human behavior...

Though incomplete as an analogy, the rat utopia does bring up many fascinating questions. For instance, what happens as we transition from post-war scarcity to material abundance? Or think about automating jobs (I'm looking at you, truck drivers). If we automate so many jobs that universal basic income becomes a necessity, how does this affect human motivation? Or happiness? Or our sense of identity?

All interesting questions. But as with any big question, our answers often reveal more about our hidden biases than rational reasoning. In other words, are we fundamentally fearful about unfettered group human behavior? Or are we optimistic about a future where we can all go play while the machines do the work?

This reminds me of the John Adams quote: "I must study politics and war, that our sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy [...] in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, and music."

So it's about motivation as we adapt to fewer external pressures. And it's about how we might transition from a scarcity to abundance mindset. And our biases about the future and our ability to change with grace.

There's a lot to be written on the rat utopia. But if we stop waxing poetic about the future of civilization for a moment, there's one question in particular that's both deeply personal and essential to how we understand our own motivation.

What do we do when we don't really have to do anything?

Until next time,

Conor

P.S. If this was at all interesting to ya, feel free to share!